On the walk to school a few months ago my five-year-old son, Samuel, asked me a question. Samuel is my second born, sandwiched between my talkative oldest and the attention-grabbing youngest. A classic middle child, he usually keeps a low profile, preferring to keep his thoughts to himself. On this day, though, he surprised me by letting me know what was going on inside his head. “Is that the cross Jesus died on?” he asked quietly, pointing to the rooftop steeple of the local Methodist Church.

Realizing what a big question came from such a small child, I blinked back sudden tears.

We walk by the church (and the cross) every day, but he had never mentioned it before. I wondered how many days he had seen that cross and wondered if a man died up there before he asked me about it. I changed the subject. I didn’t say any more, in part, because it was hard know what else to say. As a pastor who has written on children and faith formation for years, one might assume that I would have had an easier time with this moment when it came up as a parent, but I was caught off guard, and the question pointed to a deeper one: how can we talk about the cross with children in ways that are developmentally appropriate? This, I realized is an even more profound challenge when it’s your own small child.

Five-year-old Samuel is in the stage of faith James Fowler termed “Intuitive-Projective” That is to say, everything we say about faith to Samuel, he takes literally, projecting his own experiences of the world. If we were to tell Samuel that the Spirit is like the wind, he would be likely to understand that the Spirit is the wind. This isn’t necessarily problematic. After all, what a great way to see the Spirit at work in the rustling of trees and the waving of the flag? If we were to tell him that Jesus lives inside our hearts, he might have a picture of a tiny man living inside his chest. This might be more problematic, particularly if he were to have heart surgery. Would Jesus be okay in there? a child might wonder. Since my son has heard Jesus died on a cross, and he walks past a cross every day, he naturally assumed the two are part of the same, literal story. Children who are in intuitive-projective stage of faith are incapable of understanding and rationalizing symbols the way adults do. Samuel, and all children who are in the intuitive-projective stage of faith, have not yet reached a stage of psychological or spiritual maturity whereby a cross is a symbol of new life and resurrection, and because of this, we ought to reexamine our approach when teaching the death and crucifixion of Jesus.

In my experience, many pastors and ministry leaders approach the death of Jesus much too casually with children. I’ve seen Sunday school lessons for elementary-aged children that encourage they create crowns of thorns out of toothpicks and Play-Doh. Have we stopped to think about what we are instructing children to do at times like this? We’re asking them to act out the part of the crucifixion story where torturers put a crown of thorns on a person’s head in order to humiliate and hurt him. Why do we allow with this? Torture and death should not be playacted by children.

Part of the reason we are so heavy-handed with this story is because we have an unexamined theology of atonement. When we say, “Jesus died on the cross for our sins,” we are making a very specific theological statement about atonement. It is possible to have a theological understanding of Jesus’s death and resurrection that does not require the blood sacrifice of a human being as a penalty of sin. For centuries Christians have talked about what Christ’s death on the cross means, and our views have changed over time. The earliest Christians viewed the atonement in terms of moral influence. That is, Jesus came to teach us a better way to live. This moral influence theory of atonement teaches that Christ’s death and resurrection are powerful and inspiring because life is more powerful than death. When moral influence theory is lifted up as a historical and valid understanding of the atonement, the death of Jesus is talked about in very different ways. Instead of being a blood sacrifice for sins, we teach that Jesus’s death is a violent tragedy, but it was not the last word. Death has been swallowed up in victory.

We have a different view of atonement, substitutionary atonement theory, to blame for the fact we lift up the violence of Christ’s crucifixion as necessary and good. When our theology is distilled to its most basic parts in order to be taught to children, we see what we really believe. If what we believe is “a violent death saved us,” we will allow children to color pictures of it, act it out, and make it out of Play-Doh. Bloody and brutal violence is not appropriate for children simply because it’s in the context of our faith. Parents who work to shield children from gratuitous violence six days a week should not allow them to be exposed to the awful violence of the cross on day seven. It’s lazy theology and unexamined practice.

If we agree that torture and violence should not be front and center for children during the Lenten season, what approach might we take? How might conscientious ministry leaders talk about the cross with young children? Consider these practical tips:

- Stick to simple facts: Jesus died on a cross and was laid in a dark tomb. Everyone was sad and missed him. Three days later, the dark tomb was open and empty and there was light and joy. The resurrection is a mystery of our faith. There is no need to linger on details about whipping, lashing, nails, blood or torture.

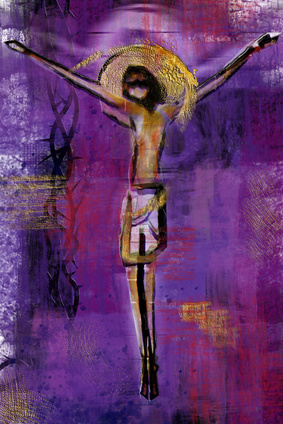

- Avoid violent images and symbols when choosing children’s curriculum. A large percentage of the materials marketed to churches for children’s use during Lent and Easter is poorly done and developmentally inappropriate. Resurrection Eggs, coloring books and children’s books often focus on thorns, crosses, nails and whips. It’s mind-boggling. Under no other circumstance would we give five year olds a coloring page with a man whipping another man. Yet, in the context of faith, many permit it, particularly during Lent and Easter. It is not developmentally appropriate for a pastor to hold up nails during a children’s message and talk about how they were driven into the hands and feet of Jesus, and yet I’ve seen this very thing, more than once.

- Be at peace with not telling the whole story. As parents and pastors we do this all the time in other areas of life. Take math, for example. In our house we have a number chart on the wall, displaying the numbers 1-100 because our children are learning basic addition and subtraction. Our children refer to it all the time when talking about addition and subtraction and counting by fives and tens. Next, I’m sure, will come multiplication and division and fractions. At some point they’ll have a greater respect for the fact that the numbers 1-100 are a mere fraction of the numbers they could know, and that numbers extend to the thousands, millions, and billions, but right now we’re focusing on the basics. “The basics” when it comes to Christian faith do not need to include the violent details of the cross. Instead, the basics of the Christian faith are these: Jesus is alive. God made the world and everything in it. God’s love is powerful. God is with us all the time, even when we are sad and lonely. A good focus for a Maundy Thursday or Good Friday children’s lesson is one about God being with us when we are sad and lonely. Another good and relevant message is that God’s love is powerful.

A challenge to ministry leaders and pastors: As we draw near to Good Friday, preparing to tell one of the most challenging narratives of the Christian faith, may we be thoughtful and wise as we consider the youngest among us. May we be very thoughtful as we choose the words we will speak and images we will show. Our children are watching and listening, more than we know (or want to believe).